Stepping Out On Faith: The Catch 22 of Business Growth

It takes money to make money, so the saying goes. Even for businesses that get started with little or no direct contribution of cash, there is always an investment of time, expertise, and other resources that can be traced back to money. But what about the self-made millionaire who pulled herself up by her bootstraps? Great! Where did she get the money to buy her first pair of boots with just the right straps for pulling? Were they given to her? By whom and how much did they pay for them? For those looking to start a new business, or leaders of existing businesses looking to do something new, it is a useful reminder that investments of time and resources are always required. But what if the idea of needing money to make money actually obscures a more important point? What if there is actually a condition that must be satisfied, or decision that must be made, before resources are invested?

The Internal Revenue Service distinguishes businesses from hobbies or charities based on their intention to make a profit and create a financial return on investment for the business owner. It is that expectation of a return, that belief that future profits will come, that must be satisfied before an initial investment is ever made. In that way, investing in business growth, innovation, and entrepreneurship are as much about faith as they are about capital management and business planning. Hebrews 11:1 defines faith as “the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen” which closely mirrors the entrepreneur and innovators’ confidence in their vision and belief in the business model that will make it possible. However, as with all things faith-related, outcomes are never guaranteed.

Jason Andrew speaks to this uncertainty clearly in his article for Medium.com, When Can I Afford to Hire My Next Employee?

“If you hire too early, you run the risk of having idle staff. They sit twiddling their thumbs with not enough meaningful work and projects to keep them engaged. If you hire too late, you run the risk of burning out your current team members with the overload of work. You risk poor-quality of work, missed deadlines, and unhappy customers.”

Similarly, for new and established firms looking to expand or innovate, their success or failure may have as much to do with the timing of their entry to the market as it has to do with the quality of their business model or idea. Ever heard of SixDegrees.com? Launched in 1997, it was among the original social networking platforms and predated Facebook by seven years, yet it failed to thrive when the market was not yet ready to embrace social networking. How about LetsBuyIt.com? They had the idea for an online group buying service long before Groupon existed, and yet they failed because at the time of their launch there was not yet a critical mass of online consumers willing to purchase goods & services over the internet.

Unless a business finds itself in the enviable position of having unlimited backing by the world’s wealthiest financiers, it will almost always be operating within a set of financial constraints. Startup firms must calculate their burn-rate and watch it closely to prevent running out of gas before they are able to generate sufficient revenue to stay in business. For established companies, this means that even profitable firms rarely have enough cash on hand to provide an open tab for expansion or innovation costs in addition to existing operations. As firms grow, the law of diminishing marginal returns dictates that incremental sales revenue will eventually equal incremental production costs. Given enough time, all businesses will find the limits of their ability to grow without making a fundamental change. They will need the benefits promised by new products, services, manufacturing processes, and even new employees that they do not yet have. Yet many firms find themselves without the resources needed to invest in the innovations and change they need to fuel future gains. That is the Catch 22 of business growth.

Business leaders cannot afford to wait on innovation or delay expansion until the law of diminishing returns forces their hand. Indeed, leaders that wait too long to innovate risk declines in sales and market share as competitors continue to push the state-of-the-art. Likewise, employers that wait to hire employees and expand their operation until they are forced to take action risk lowering employee productivity and taking on excessive turnover costs due to burnout. Both outcomes can easily leave already struggling firms with even fewer resources available to address their situation. So, when is the right time to take that leap of faith? It turns out that the best time for leaders to make a change is typically when they least feel the need for it.

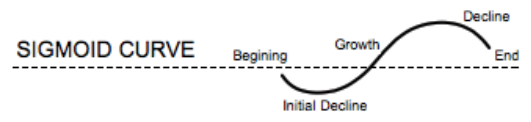

Organizational leaders, theorists, and researchers have observed a consistent pattern when examining organizational life cycles from inception to termination and how they respond to change. An initial period of slow growth or operating losses eventually gives way to rapid growth as the organization finds traction and produces results. The robust growth phase results in rapid gains and an enviable upward trajectory. Eventually, however the law of diminishing marginal returns takes hold, slowing the rate of growth and leading to decline. This trajectory can be modeled as a logistic function and graphing it over time results in the Sigmoid Curve (depicted below). For leaders looking to maintain growth over time and manage change to their advantage, this curve offers useful insight into the right time to push for innovation, change, or expansion.

Organizational Life Cycle diagram (Hipkins and Cowie)

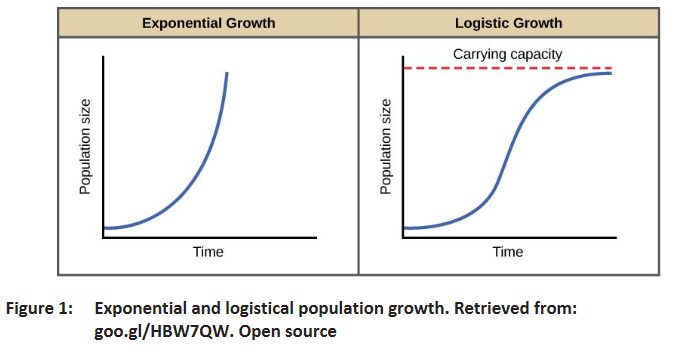

In making the case for the sigmoid curve as a useful metaphor for growth and change, Hipkins and Cowie point to the work of economist Thomas Malthus who successfully showed that sigmoid growth curves emerge because systems or marketplaces are bound by limits. For Malthus’ work, the carrying capacity of the environment served as a population limit (see figure 1 from Hipkins and Cowie). For businesses, market saturation, production limits, pressure from competitors, and other factors serve the same function.

Figure 1: Hipkins and Cowie

Malthus predicted that human birth rates would exceed the growth rates of food and resource supplies, eventually causing the population to exceed the carrying capacity of the earth and leading to mass starvation until enough of the population perishes to restore balance below the carrying capacity limit. Fortunately, this did not happen. Instead, advances in agriculture kept pace with population gains and continuously increased the globe’s population carrying capacity from the late 1700’s into the modern era. This ultimately led to an explosion of agricultural technology and food production gains in the early 1950’s, and ‘60’s known as the Green Revolution.

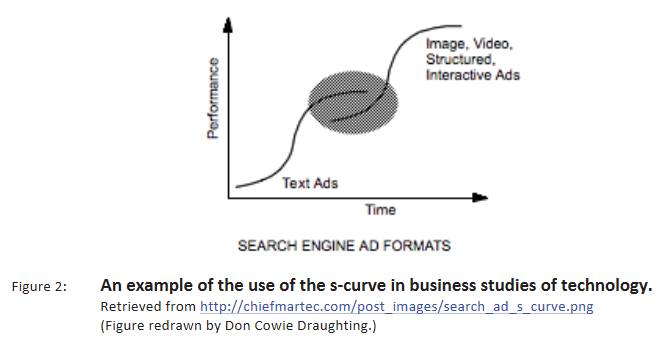

There are always limits within any given system. However, the Green Revolution and the advances that preceded it show clearly that they are not immutable. Limits can be changed through technology, innovation, and market forces. This change causes new growth curves to emerge and replace previous trajectories for the organizations and businesses at work within their system or market (see figure 2 from Hipkins and Cowie).

Figure 2: Hipkins and Cowie

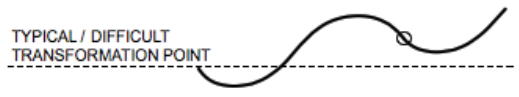

At some point, nearly every business leader has felt like the rules of the game have shifted on them. Mapping that feeling onto the organizational lifecycle’s s-curve, it is clear that the mostly likely time for leaders to experience this is after growth peaks and the organization begins to decline (pictured below). Leaders who successfully guide their organizations through this phase realize quickly that the rules of the game have changed and respond by transforming their organization to recover their momentum.

Turning around a decline, leading through the dip, and restoring growth is difficult. After guiding their organizations safely through crises, it would be natural for leaders to celebrate or even breathe a sigh of relief. However, it is also worth asking whether the stress and uncertainty of the decline was really necessary. Rather than waiting until circumstances force one to cope with change, what would it look like to lead and initiate change before the organization experiences a decline? How can leaders recognize the right time when it comes?

Organizational Life Cycle Typical Transformation Point: Hipkins and Cowie

To put it simply, the ideal time to initiate change, look for what’s next, and even hire new employees is precisely when the organization feels the least need to do so. The right time to innovate, expand, and change has little to do with when the current model stops working or how busy the firm’s current employees are. Anyone who has been part of a declining organization can attest to the fact that being busy is not the same as being productive. Instead, the right time has everything to do with the timing that is most likely to stack the deck and tilt the odds in favor of the firm. That occurs at the midpoint of the growth cycle; when everything seems to be working, all cylinders are firing, a clear pathway for continued growth lies ahead, and there seems to be absolutely no reason to look for change.

Organizational Life Cycle Ideal Transformation Point: Hipkins and Cowie

Organizations that innovate and change in the middle of their growth phase maximize the time they can devote to innovation as well as their financial, operational, mental, and emotional resources. By initiating change when the firm’s current business model is at its most productive, they are able to effectively subsidize their development costs and insure that the next great innovation is ready to generate traction and take off just as the current model begins to decline.

Despite the arguments in favor of early change and innovation, few organizations embrace them in practice. Most leaders don’t start thinking differently until their organization is in decline. Why? Because investing time and resources to think about change when things are going well doesn’t feel like the sensical thing to do. For company founders who worked hard to guide their organization through its initial startup, it feels particularly wrong to divert resources to invest in developing new business models just when all the hard work and sweat that went into the first one is starting to pay off!

Leaders must be aware that those who advocate for change and innovation when everything is going well should expect heavy resistance. They can expect to be called foolish and to hear variations on the theme of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” coming from multiple corners of their organizations. If they are lucky, such criticism will come in a form that can be productively addressed. More often though, such comments will be whispered in hushed tones and private conversations that remain hidden from view but that nonetheless have a profound impact on the organization and its culture. In contrast, leaders who successfully turn around organizations after they are in obvious decline have a shared mandate for survival. Rather than change appearing foolish, they are hailed as organizational heroes courageously fixing what was broken. They are given the mantle of business sage and lionized in company lore for successfully battling against decline.

However, for leaders who are more concerned with the wellbeing and success of their organization than they are about the drama of their future biography, the benefits of avoiding decline are compelling. Done well, successfully avoiding a fall into decline will remain largely invisible to the bulk of one’s organization. Most employees will experience it as simply an extended period of growth. Leaders who employ it accept and even celebrate that guiding their organization to avoid a crisis will rarely win them accolades for their response to the crises that didn’t happen. But it will make a positive impact and position their teams to continue to grow.

As a model, the organizational lifecycle is an effective tool to communicate the context and motivation behind continued advocacy for innovation and change when the organization seems least likely to need it. As professional poker players will tell you, the time to place big bets is when you don’t need the cards to flop your way in order to make your mortgage payment. Leaders can use the s-curve to share their vision and show others why it is critical to continue investing in innovation after achieving success.

Optimizing growth over time requires leaders to innovate, expand, and rethink their businesses well before circumstances force them to do so. Taking a leap of faith and driving innovation in the growth phase when everything is going well can be hard to do, but it is worth it in the long run. The sigmoid curve of the organizational lifecycle helps leaders inform their decision-making, guide their change efforts, and communicate their rationale. Leaders that understand and apply it to in their businesses are better positioned to avoid the Catch 22 of business growth and make their leaps of faith when they have the best odds for success.

Knowledgeable guidance helps, but no one can do it for you.

Let’s get to work!

References:

Andrew (2018). When Can I Afford to Hire My Next Employee? Part 1. Medium.com

Andrew (2018). When Can I Afford to Hire My Next Employee? Part 2. Medium.com

Hecht (2014). Does It Really Take Money to Make Money? Inc.com

Kucharavy and De Guio (2011). Application of S-shaped curves. Procedia Engineering

Matthews (2018). Five Reasons Companies Fail. Entrepreneur.com